Game Sprint 4: Catching Wind and using Composition

July 13, 2025

Catching Wind was the easiest game for me to develop and the least polished Game Sprint game to date. Let's talk about that.

Since starting this project, I've avoided making a platformer. Not because I thought it would be difficult, but because I feel like it would be a copout. The bones of a platformer are exceptionally easy to build, and with the amount of dev time in a Game Sprint, it's hard to bring something new to the genre.

It's why I set aside my wind-based platformer idea for this past fortnight, when I knew I'd be far busier than in the prior month and a half.

What a surprise that when something is "easy", it's far easier to procrastinate! I knew that the challenge of making consistent progress on a game every day only for the knowledge that it will help me build something truly great an indeterminate time from now would present itself soon enough, and I'm glad it was this early on in the process.

Unlike the other games I've made, Catching Wind has no title screen, no sound effects, no music, and no assets designed by myself. Its release even had to be pushed back by a day — to Monday (the horror!). It's also the shortest game I've made, having only five levels (all of which were designed today, in engine).

I'm not proud to admit all of that, but games like Catching Wind are an important part of this project, which is designed above all else for me to learn the craft of game development through consistent, structured practice rather than deliver the best games.

Still, I spent far less time working on Catching Wind than I'd planned, so let's take a step back and talk about how that happened, and what you and I can learn from it.

The first thing I didn't do was plan this game. I sketched out the core gameplay loop on paper, but I never made a GitHub project with tasks to complete. This meant that development lacked focus — still following the daily structure of a Game Sprint (something I plan to write a more detailed post about for others who want to try my game-oriented version of Agile), but without the broader Sprint planning that makes dividing tasks for each day possible.

Without a backlog, there were no tasks I wasn't completing, just the nebulous "rest of the game" to build. Breaking down every task that needs to be completed for a game's release makes development less daunting, and prevents procrastination. Even for an "easy to make" game, planning is crucial.

The second thing I didn't do was design gameplay before working on implementation. This is unusual for me, as sketching levels and mechanics on paper is a core part of my development process, but again the simplicity of this game saw me making one sketch before building the game, only designing levels in engine today.

I have lots of excuses that I could present here, but I'm too principled to stoop to that low!

Oh look! A boat on which I spent a third of this Sprint helping my cousin with renovations! How did that get there?

Anyways.

I'm still proud that I delivered a game, and I've learned a lot from these past two weeks.

So let's talk about it!

Platformers and Composition in Godot

It turns out that platformers aren't so simple after all! A huge shoutout to Mark Brown of Game Maker's Toolkit for his brilliant playable essay about all the hidden mechanics involved in making a character jump around in a satisfying way. Even if you're not at all interested in making games yourself, If you like platformers, I strongly suggest you give it a play.

I don't want to take away from your experience playing, but here are just a few of the mechanics I hadn't considered:

- Coyote Time — a brief window of time in which players can jump after they've left a ledge, making the game feel less punishing and more natural.

- Variable Jump Height — by holding down the space bar for more time, players can control how high the character jumps.

- Down Gravity — making characters fall faster than they rise when jumping.

I implemented all of these mechanics using Composition, a paradigm that I don't recall having ever been discussed throughout my undergraduate in Computer Science, but one that feels far more suited to building games than Inheritance.

With Composition, instead of building classes with a hierarchy of inherited functionality, you build classes comprised of other classes that perform some function to those components. For example, an Inheritance-structured button that plays a sound effect and triggers a scene change on click might be structured Button, inherited by SFXButton, inherited by SceneSFXButton where the SFXButton class would make building all future buttons simpler (avoiding the need to add and configure an AudioStreamPlayer to each manually), and the SceneSFXButton would @export a PackedScene which would be loaded on click. A Composition-structured SceneSFXButton might instead be structured Button, parent of SFXTrigger and SceneTrigger, where each child of the button might either @export a signal to trigger their respective functions or contain a reference to their parent Button, attaching functions to its signals.

The latter approach means classes can be both smaller and more bespoke, while also being far more generally usable. For example, unlike with most of my previous Sprints, I plan on carrying forward nearly all of the classes I designed for future projects, as I know they can be dropped in without much, if any, reconfiguring.

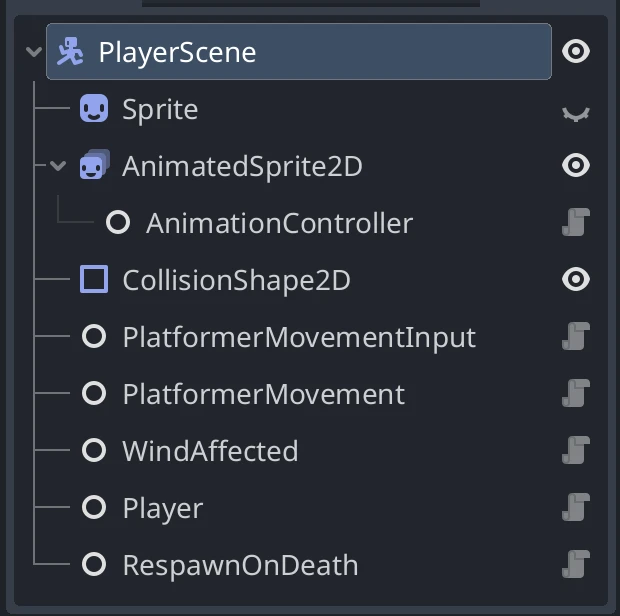

Let's take a look at the player character from Catching Wind:

As you can see, the PlayerScene comprises many classes — each of which are just tiny nodes that serve a singular function, adding functionality without sacrificing modularity or increasing coupling. Another platformer could be made with the same PlatformerMovement and PlatformerMovementInput components, with the wind mechanic entirely separate and removable. The stats resource that governs movement is the same resource used by Wind objects to determine how they affect other bodies. Further, WindAffected is a component that can be added to any object, allowing the same component to be used for any objects in the game that can be blown by wind.

Even with a small project like this game, Composition immediately led to far less hunting through scripts to tweak functionality and far more clarity about which components did what.

Here's the code for my WindAffected node:

class_name WindAffected

extends Node

@export var body: CharacterBody2D

@export var platformer_movement_input: PlatformerMovementInput

var wind: Wind

func _physics_process(delta: float) -> void:

if platformer_movement_input == null and wind != null:

body.velocity.x = move_toward(

body.velocity.x,

wind.stats.max_speed,

delta * wind.stats.acceleration)

func set_wind(new_wind: Wind) -> void:

wind = new_wind

if platformer_movement_input != null:

platformer_movement_input.stationary_velocity = new_wind.stats.max_speed

func remove_wind(old_wind: Wind) -> void:

if wind == old_wind:

wind = null

if platformer_movement_input != null:

platformer_movement_input.stationary_velocity = 0.0

This class takes a CharacterBody2D and an optional PlatformerMovementInput and either passes off a wind velocity to it or handles that wind velocity itself. Here's the companion Wind node — but notice that the WindAffected class does not need to know anything about the Wind class other than that it has a stats resource.

@tool

class_name Wind

extends Node

@export var area: Area2D

@export var stats: MovementStats

@export var particles: GPUParticles2D

@export var shader: Node2D

func _ready() -> void:

area.body_entered.connect(_apply_wind)

area.body_exited.connect(_remove_wind)

if particles != null:

particles.process_material.set(&"direction", stats.max_speed)

particles.speed_scale = abs(stats.max_speed) / 200.0

if shader != null:

shader.material.set("shader_parameter/speed", stats.max_speed / 50.0)

func _apply_wind(body: Node2D):

var wind_affecteds: Array[Node] = body.get_children().filter(func(node):

return node is WindAffected)

for wa in wind_affecteds as Array[WindAffected]:

wa.set_wind(self)

func _remove_wind(body: Node2D):

var wind_affecteds: Array[Node] = body.get_children().filter(func(node):

return node is WindAffected)

for wa in wind_affecteds as Array[WindAffected]:

wa.remove_wind(self)

This class contains all the code necessary to add windy areas with stat-driven visual feedback, and all it needs to know about WindAffected objects is that they have set_wind and remove_wind functions.

Still, this code could be further decoupled — WindAffecteds could instead have a wind_stats variable, preventing them from needing to know anything about Wind, or Wind and WindAffected could be rewritten to make WindAffected more like a tag, passing off movement behaviour to the Wind itself (enabling more unique Wind behaviour), but I hope the above example shows how simple and extensible Composition can be.

The benefits to code complexity aside, the ability to design functionality by assembling sets of small, modular nodes makes it far easier to understand what each component in your game is doing, as well as easily add and remove functionality from objects.

Thanks for reading this Sprint's devlog. I'm taking a temporary break from Game Sprints until 2026 as I've taken on a research position in Internet Censorship as well as a Teaching Assistant position in Game Development. See you in February for my fifth Game Sprint game: Paper Racers!